An Unsentimental Education

Alice Munro is badass because her characters are passionate but never sentimental. Children leap to their deaths and drown the dog while they’re at it. Nieces coolly despise their maiden aunts and then get bitch-slapped by a revelation from the aunt’s bastard child at the aunt’s funeral. Everyone is wreaking havoc on everyone else but Munro doesn’t allow anyone to complain about it. Not in her pages, anyways. What her characters do outside of her books is their own business.

I was surprised and thrilled to read in an interview that Alice Munro is crazy about Eudora Welty. Munro says:

I still [adore Eudora Welty]. I would never try to copy her—she’s too good and too much herself.

I am crazy about Welty, too, but I never would have paired the two because Munro, in my mind, is spare and exacting; whereas Welty is sprawling and outrageous. Neat rows of cornfields vs. kudzu spilling all over; a razor-sharp interior monologue vs. a family interrupting each other at the dinner table. In Munro’s southwestern Ontario, speaking out of turn is a sin; whereas in Welty’s Mississippi Delta, the storytellers are the blessed ones. The fictional characters created by Munro and Welty, respectively, differ as dramatically as the characters of the two women themselves. This stems, in part, from their separate geographies. From what Flannery O’Connor rightly referred to as the “mystery and manners” of a region, and what Lionel Trilling called “a culture’s hum and buzz of implication.” “She’s too much herself,” Munro says of Welty, as Welty, I’m sure, would have said of Munro. There is no higher compliment for a fellow fiction writer.

But just because you can’t – and shouldn’t – copy your writing crushes doesn’t mean you can’t learn buckets from them. Reading Munro, I am reminded that every evocative line of prose must be deeply earned; you can’t just waltz in and throw epiphanies on every other page because they have a nice ring to them. Reading Welty, I am reminded how weird people are, and how agonizingly specific they are in their weirdness.

Take the first paragraph of my favorite short story of all time, “Why I Live at the P.O.” which appeared in Welty’s 1941 collection, A Curtain of Green:

I was getting along fine with Mama, Papa Daddy and Uncle Rondo until my sister Stella-Rondo just separated from her husband and came back home again. Mr. Whitaker! Of course I went with Mr. Whitaker first, when he first appeared here in China Grove, taking “Pose Yourself” photos, and Stella-Rondo broke us up. Told him I was one-sided. Bigger on one side than the other, which is a deliberate, calculated falsehood: I’m the same. Stella-Rondo is exactly twelve months to the day younger than I am and for that reason she’s spoiled.

So weird. So good. Munro does not have Welty’s breathless humor; Munro’s characters crack each other up but do not necessarily include the reader in their jokes.

As a fiction writer, I find it hard to steer clear of the sentimental. It’s like a nervous laugh or an unfelt compliment: there to fill the silence. But for Munro, sitting on the edge of the abyss, having your legs cheerfully dangling into the void, is the whole point.

(Although that image – the cliff, the void – would probably irritate her: why not a wooden bridge, she would ask; why not a fast-moving stream?)

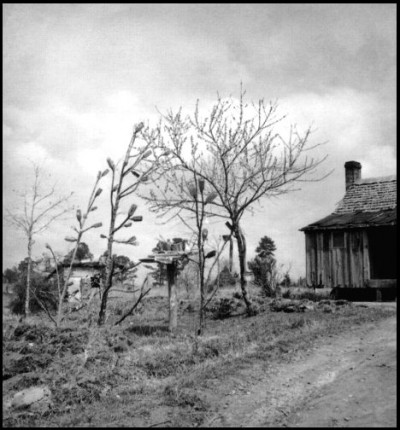

(Photo of “bottle trees” by Eudora Welty)