Being Marx and Engels in China

WeChat or 微信 Weixin is one of my favourite things in China. It’s like WhatsApp plus social networking, only better in a Chinese way, and has about 300 million users. After a night of running around and away all over Beijing in August, from strangely luxurious basement hotel bars on the outskirts of the city, where I meet Julien, who in his French-Chinese accent can only say he is “a bit tipsy” before falling down, to unstable rooftops filled with people in drag, Ai Weiwei’s assistant Marlene texts me and asks if I would be available for some voice over work for a Chinese artist who is doing a new film. For some reason, I say yes. I have never done this before. She is asking for a friend. Her friend later texts me. She is also asking for a friend. It takes a while until the whole thing begins to take shape. It will be on my last day in China after a long time I spent there this year. I still don’t know what exactly I am supposed to do, or where. A few days before, the artist Qiu Jiongjiong emails me a script and asks me to translate the dialogue into German. Finally, I realize that I am going to be the voice of Karl Marx.

As the day arrives, I have translated the script into German, which is a dialogue between Marx and Engels as they watch the long march of Chinese prisoners of war, arranged a fee, and another friend of the artist, who barely speaks any English texts me an address. I take a cab, the driver speaks the best Beijing accent and we absolutely do not understand each other. At some point, he just lets me out and I find myself in northern Beijing, surrounded by highrises and construction sites. I feel frazzled. I send the friend of the friend of the friend a WeChat voice message – most people do that instead of calling – and we try to locate me. I try to pass the phone to passers-by, who suspect some kind of prank or other weirdness and evade me, one of them squeaking and running away. It takes a while, but I get picked up. We walk. She studies documentary film and is working on a PhD on independent documentaries in China, which she will never get published, she says, it won’t get past the censors.

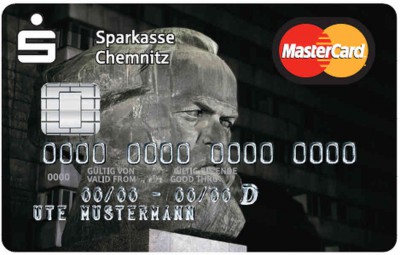

Qiu Jiongjiong’s apartment is on the 10th floor of a typical Beijing apartment complex. Sort of shiny, with four elevators, each of which is either broken, an empty lift shaft, or basically made of wood. The hallways put MC Escher to shame. Qiu Jiongjiong lives and works there. The sound engineer is an extremely good looking girl. We enter the studio, which as it turns out is the room of Qiu Jiongjiong’s daughter. Mattresses and pillows barricade the windows, toys in neon smile. We do a few tests and checks. I didn’t bring a printout. I have to stand perfectly still and balance my laptop on my arm to read the dialogue. I feel like a socialist statue. My arm starts shaking. We start recording, we communicate through nods, and the student sometimes translates his directions. Again. Deeper. Heavier. After we are done with the Marx part, they ask me to do Engels, too. With a lighter, younger voice. Qiu Jiongjiong looks very serious but is totally enjoying himself. Marx and Engels in China now have an Austrian accent.

The whole thing takes only twenty minutes. I decide to refuse getting paid. Instead, I get a few books and DVDs, an apple, and 50 kuai for a cab. Evening is sinking on the city. A Maserati is slowly making its way through the narrow hutong streets, millimetres away from people having dinner. Somewhere, a Chinese man is singing Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah”. Before I go to bed, I sit on a rooftop again. As it starts to rain, my friend Xinxin demonstrates her newly acquired tap dancing skills in slow motion.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QWMIRkTs8Aw