Shaky Omniscience

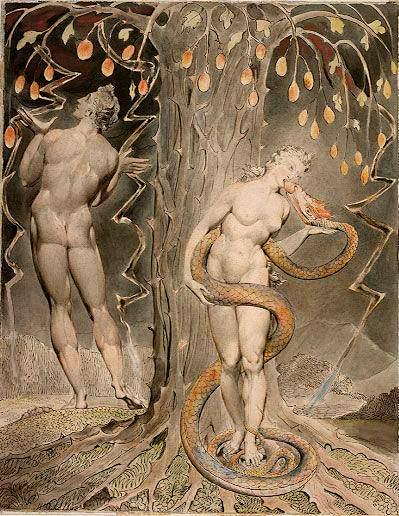

(William Blake, The Temptation and Fall of Eve)

It’s a creative writing workshop mantra that even if a character doesn’t know something in a story/novel, the writer needs to know it. But is this really true? Is there any way that the character’s ignorance and the writer’s ignorance can mingle and create greater mystery? Must the author always peek behind the curtain, just because they can?

I brought this topic up over dinner and there were several responses. Some people said the author needs to be all-knowing. (The “it’s called omniscience, idiot” line of argument.) Then there was the Buddhist argument, as one writer put it, that if you need to know, you will. “If you don’t know, who does?” asked another fiction writer, and I considered that a good question — by no means a rhetorical one.

In Deborah Treisman’s interview of Alice Munro in The New Yorker last year, Munro states that

In “Leaving Maverley,” a fair number of people are after love or sex or something. The invalid and her husband seem to me to get it, while, all around, various people miss the boat for various reasons. I do admire the girl who got out, and I rather hope that she and the man whose wife is dead can get together in some kind of way.

What does it mean for an author to “rather” have this “hope”? Doesn’t she know? This example is slightly stilted, as it concerns the afterlives of characters, their post-novel romps, but the point is, it underlines Munro’s (and all of our) shaky omniscience as authors.

What interests me is when (and if) it pays off to be just as clueless as your characters. I understand that this is affected by which perspective (first, second, third, etc.) the fiction is being written in, and many other factors. I would love to bring more examples and interviews and the categorical imperative into the mix, but it’s past midnight and I haven’t packed for Thanksgiving and I’m leaving tomorrow morning at 6am. So for now, the subject will have to remain rather oblique. Which, given the topic, seems only appropriate.