Sino-Cybernetics, pt. 2: Frank Lloyd Wright, Daoism, Engineering, and Orson Welles.

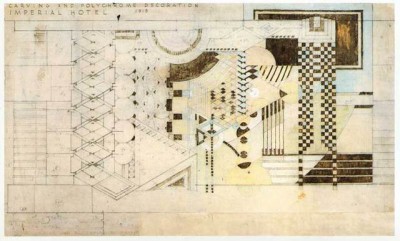

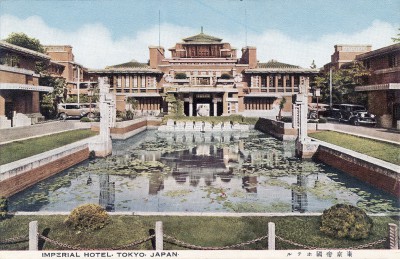

In 1934, an already middle-aged wunderkind by the name of Norbert Wiener embarked on a journey by ship from California to China via Japan. He had been invited to teach mathematics and electrical engineering at Tsinghua University in Beijing, by a former MIT graduate student of his by the name of Yuk-Wing Lee. Wiener thoroughly enjoyed staying at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, “that fantastic structure of the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright”, as he notes in his autobiography. “The hotel was excellent and the food very good, but in those days the guests were subject to continuous surveillance.”

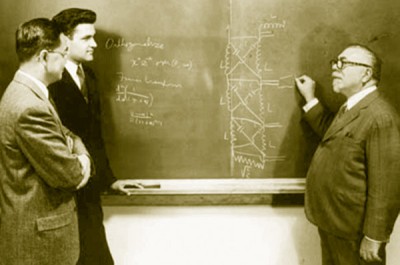

Upon arriving in China and continuing for Peiping or Beijing by train, Wiener notes that the landscape is “reminiscent of the cornfields of Kansas”, even though he had a feeling they were not in Kansas anymore. Tsinghua University in the Republican Period under the Kuomintang was a very international place. There have always been small windows in time when East and West were freely exchanging knowledge. The early 1600s, and between World Wars. Even before Wiener took up teaching, he started taking private lessons in Mandarin together with his wife. His children, as children do, picked it up from their playmates on the streets. They brought home a small red cat and named it Pao. For Lee and Wiener, this proved to be a very productive and formative time. They developed several innovative circuit designs for electrical networks and set out to design one of the first analogue computers. Here is a photo of the two ca. twenty years later – they continued to work together for the rest of their lives:

What I am trying to emphasize here is the role that Wiener’s time in China played in the development of computing apparatuses and the science and philosophy of Cybernetics – the idea that feedback mechanisms govern everything. Cybernetics, it seems, is strongly influenced by what Wiener learned about the Chinese philosophy of Daoism, the teachings of the Way, of Eternal Return, of Processuality, Harmony, and Balance. Lee and Wiener developed a distinctive and notorious style of drawing circuit diagrams and it stands to argue that Chinese writing shaped the way they dreamed of networks.

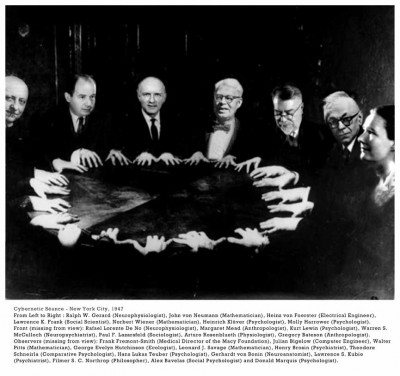

In Beijing, I met a Chinese historian of science – a specialist in the early history of quantum mechanics in Austria -, who told me about an old professor at Tsinghua, almost 90 years old, who seems to be the only other person I know so far convinced that Cybernetics was a Chinese inspiration. I have yet to find a way to communicate with him, since he is very old, speaks only Chinese, and my Chinese is definitely not sufficient for discussions about this. I traveled from Beijing to Boston last year to forage through Wiener’s archived life at the MIT, dreaming of finding hand-drawn circuits next to Chinese characters, growing into each other like vines, being hard-wired… I did find tons of patent applications Lee and Wiener had prepared for AT&T and Bell Systems. Moreover dozens of letters from the 1930s-1950s detailing Wiener’s deep involvement in Chinese affairs from the Sino-Japanese War through World War Two, including correspondence with Zhao Yuanren, about whom I wrote here yesterday, and whom Wiener invited to join the Macy Conferences.

I signed a waiver that I would not publish the copies I made at the MIT. Otherwise I could show you the handwritten limerick young Norbert wrote about having to go to college:

And to walk every morning a mile

To a nine o’clock lecture is vile

The thermometer then

Is a scant minus ten

And a hurricane blows all the while

And so on… I would also show you the handwritten manuscript of the 1948 Cybernetics, Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, on the title page of which Wiener misspells both “Communcation” and “Mahematics”. Or the very long letter he wrote to Orson Welles in 1941, after he had watched Citizen Kane. It is not only a nice critique of Welles’ work, but also a movie pitch: Wiener draws a vivid insider picture of the world of electrical engineering, its 19th century history, the “War of Currents”, the fights for patents and telegraphic network hegemony, all of which was distinctly “noir”, and the way it was to shape the 20th century and world of tomorrow. He tried to convince Orson Welles to make it into an epic, surpassing Citizen Kane in its portrayal of Media and Iconicity. I could not find a reply by Mr. Welles.