The Devil’s Ballroom

“Below the 40th latitude there is no law; below the 50th no god; below the 60th no common sense and below the 70th no intelligence whatsoever.” Kim Stanley Robinson

“The Devil’s Ballroom.” Roald Amundsen about Antarctica

Of all the utopian fantasies of the 19th century, the exploration of the South Pole has been for its prewar beginnings what the journey to the moon was to become for its postwar coda. All the explorative aspirations of a world that was about to crumble, all the desires of collapsing empires were drawn towards this most abstract of spaces. Magnetic poles are, after all, attractive by definition.

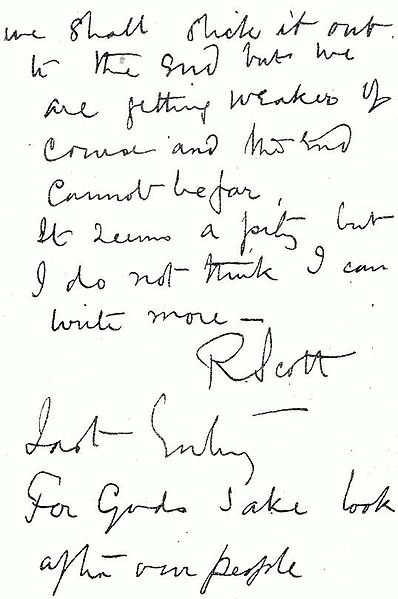

Maybe reaching one end of Earth’s axis could halt the inexorable decay of the world and its systems. Maybe its motion could be set straight, controlled even. Whoever would be able to plant a flag there, in the midst of the terrors of ice and darkness, to mark a spot that science had said would be there and that only the death-defying endurance, grit and ingenuity of man could reach, would make history. It would be the end of history. No further expansion: there is nothing south of the South Pole. Empires would become frozen in time, eternal.

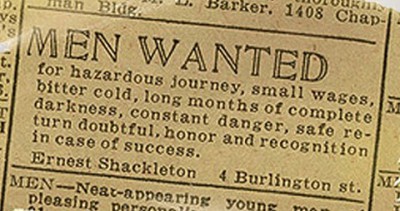

The race or war for the South Pole was the real Cold War. During what came to be called the “Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration”, 17 major expeditions from 10 countries were launched. Besides the three big names that polarized the race for the pole – Roald Amundsen, Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton – many illustrious captains and countless nameless crew headed for these realms that were and still are not of this world anymore. Jean-Baptiste Charcot, for example, son of Jean-Marie Charcot, inventor of Clinical Psychiatry who had launched Freud’s explorations into the inner workings of Man (how else could we have become bi-polar?), shipwrecked and died with his vessel aptly called Pourquoi-Pas? The first Japanese expedition was led by Shirase Nobu, and army officer with a face chiseled from granite and a sense for dress. They were the first humans to make a landfall on the Edward VII Peninsula and were celebrated as heroes upon their return to Japan.

Apart from being the first, what became increasingly important during this time when all the major global players set out to colonize the ice was how they did it. The idea behind it, the method, the technology and equipment used and, most importantly, the particular style of these extraordinary gentlemen. Granted, the expeditions were also massive media events, which sold newspapers and adventure books and filled lecture halls; but that wasn’t the only reason why style was important.

More importantly, developing distinctive features in their way of dressing reflected their “lines of attack”, one might say. After all, the very last thing that kept a man from dying and becoming part of the eternity of ice was the way he dressed (and if he did die, he would at least make for a “good looking corpse”, long before and long after James Dean). Amundsen preferred an intricate patchwork of fur that would keep him warm during the long hours on the dog sled, dancing through the “devil’s ballroom”, as he called Antarctica. “Not an outfit that cut a dash by its appearance, but it was warm and strong”, he wrote. Sealskin suits and boots designed by Amundsen himself, Inuit-inspired clothes from reindeer and wolf skin, Burberry cloth and gabardine dressed his party for the hardships ahead. Scott swore on layers of tight-knit wool to keep warm and oilskins or waxed cotton as a weather-proof outer layer. He did not believe in the style of the native people of comparable regions up North, however he wrote: “One continues to wonder as to the possibilities of fur clothing as made by the Esquimaux, with a sneaking feeling that it may outclass our civilised garb.” Carsten Borchgrevink relied on the Lapps’ method of insulating his boots with “sennegrass” instead of wearing socks. Sennegrass is certain kind of sedge which creates warmth when arranged around the feet inside the boots, while absorbing sweat. When Shackleton’s ship Endurance became trapped in pack ice and was slowly crushed, a well-kept stash of costumes helped pass the time and keep morale high, when the crew turned into the southernmost theatre company of all time.

But for the incredible journey that Shackleton and his crew would still endure, pilot cloth and Jaeger fleece remained flexible enough in the extreme cold. The most important stylistic feature, however, which would prove crucial for success and survival in these pastures, was to mimic the paradoxical nature of Antarctica itself. It would seem that this no man’s land was rigid and frozen, crystalline to the utmost extreme. But at the same time, the ice was the most dynamic and dangerous ground imaginable, ever changing, moving, suddenly opening to swallow everyone who dared to tread on it. The explorers needed to be stable and unstable at the same time, just like their surroundings. Massive and strong like polar bears, yet swift and agile. The exploration of Antarctica continues until today, because, metaphysically at least, there is something south of the South Pole.

Originally published in Modern Weekly China, 2013.