The End of Philosophy

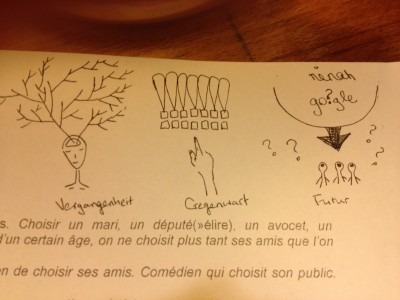

Yesterday was my final philosophy class, which I celebrated by taking the wrong subway and arriving half an hour late. The Korean girl had just delivered a presentation on choice, to which nobody was responding, despite Reinhard’s gentle prompting. I asked for a copy of the handout she’d distributed. On the top was a beautiful illustration of a person with a tree sticking out of their head (the past), then a computer keyboard with bubbles leaping up from the top keys (present), and then what looked to be aliens under a Go?gle sun (Future).

After an uncomfortable silence, the brunette American woman spoke up and began describing how often Zalando boxes get delivered to her apartment building and how her friend lets her kid play with an iPhone. She spoke like a prophet: unhalting, assured, and endlessly. I was mesmerized by her hands. They were long and slender, and the nails were immaculate, painted a translucent pearl. I wondered how I would behave with hands like that. With those kinds of nails, I thought, you would weigh your choices more seriously. You wouldn’t let those nails down by eating messy sandwiches on the subway or wearing old underwear. She kept lifting up her smart phone and shaking it for emphasis. Her German was beautiful, nearly unaccented, and in the middle of a sentence she turned to me and said, “tailored to our tastes, you know,” in English, and then landed on “geschneidert,” and kept going.

In the wake of her speech, the room lapsed into silence again. Reinhard said, “Na gut,” the way a preacher says “Amen,” and distributed a sheet with quotes from Goethe.

“Wir schätzen die Gegenwart zu wenig, tun die meisten Dinge nur fronweise ab, um ihrer los zu werden. Eine tägliche Übersicht des Geleisteten und Erlebten macht erst, daß man seines Tuns gewahr und froh werde, sie führt zur Gewissenhaftigkeit. Was ist die Tugend anderes als wahrhaft Passende in jedem Zustande? Fehler und Irrtümer treten bei solcher täglichen Buchführung von selbst hervor, die Beleuchtung des Vergangenen wuchert für die Zukunft. Wir lernen den Moment würdigen, wenn wir ihn alsobald zu einem historischen machen.”

“We value the present too little and perform most tasks only grudgingly, in order to get them over with. Only by conducting a daily overview of our achievements and experiences will we become aware and glad of our actions; this overview leads to conscientiousness. What is virtue other than arriving at a truthful compatibility in each situation? Mistakes and delusions emerge spontaneously with such daily accounting, the illumination of the past sprawls into the future. We learn to honor the moment when we treat it as a historical one.”*

Looking back on yesterday’s philosophy class with the scrutiny that Goethe proposes, I admit that I may have lapsed into a too flippant tone, which I often do in the face of seriousness, be it a tender philosophical passage or a somber leave-taking. I didn’t tell Reinhard how much I had enjoyed the class or apologize to him for being late: I spoke breezily about my upcoming residency in Virginia and said I would hopefully see him in February, when the next class begins. I dread earnest, elongated goodbyes, which too often feel like spilling something on the floor and then trying to wipe it up. I wonder how Goethe said goodbye.

Reinhard told us that Goethe was a Genießer, a sensualist, and so I imagine his daily “accountings” to be have taken place in soft, yellow lamp light rather than the uncompromising glare of midday. Like a child building a fort in the woods, then stepping back to appraise his construction, trusting his own eye to tell him where to add sticks, where to take them away, what will best shelter him.

*Hasty translation my own; thanks to Erwin Schmidt for his help.